- What is the Via Dolorosa?

- Station 1: Jesus is condemned to death

- Station 2: Jesus takes up his cross

- Station 3: Jesus falls for the first time

- Station 4: Jesus meets his mother

- Station 5: Simon of Cyrene helps Jesus

- Station 6: Veronica wipes the face of Jesus

- Station 7: Jesus falls for the second time

- Station 8: Jesus meets the women of Jerusalem

- Station 9: Jesus falls for the third time

- Station 10: Jesus is stripped of his garments

- Station 11: Jesus is nailed to the Cross

- Station 12: Jesus dies on the Cross

- Station 13: Jesus is taken down from the cross

- Station 14: Jesus is laid in the tomb

Every year, millions of Christians make the pilgrimage to the Holy Land to walk in the footsteps of Jesus. One of the many attractions they will experience is the Via Dolorosa. Or The Way of the Cross. Pilgrims will carry a wooden cross through Jerusalem’s Old City as they honor Christ’s sacrifice for our sins.

But what is the Via Dolorosa? Latin for the “Sorrowful Way” or the “Painful Path,” the Via Dolorosa is the traditional route that Jesus carried his cross from where he was condemned to death by Pontius Pilate, to Calvary. The route ends at the tomb of Christ. It consists of 14 Stations of the Cross which commemorate different events that happened along the way.

Today the Via Dolorosa starts near the Lions Gate at the Omiraya School, which sits on the spot where scholars think the Antonia Fortress once stood. And it ends at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre which houses both the mound of Calvary, otherwise known as Golgotha, and the Tomb of Christ itself.

Walking the Via Dolorosa can take anywhere from 45 minutes to about an hour and a half. It depends on your tour guide and what he or she talks about at each station. If you are walking it on your own, without stopping or dealing with pedestrian traffic, the route takes about 15-20 minutes. (Check out my 6-minute detailed walkthrough of the Via Dolorosa.)

The procession hasn’t always started at the Omiraya School and ended at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre though. Nor has it always followed the same route.

Even more surprising is how the route was established and why it was started in the first place.

Note: All links are direct. All bible verses are linked to Biblegateway.com.

Why is the Via Dolorosa important?

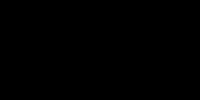

In the Gospel of Mark we get the most dramatic and descriptive commentary on Jesus’s path to the cross. Mark was writing to gentile Christians living in Rome, which meant they grew up in and saw life through Roman society and Roman traditions. Many scholars have noted that Mark’s description of Christ’s crucifixion procession is similar to the Roman triumphal march that celebrated a victorious general or emperor.

As a result, the importance of the Via Dolorosa procession is that it celebrates Christ’s sacrifice and triumph on the cross.

Originally, the Roman triumphal march proclaimed victory for a military conquest. The general’s soldiers would declare him a victorious general imperator and the senate would decree a Triumph.

The general would take the title of Triumphator and then appear in the triumphal robe, which was purple in color (sometimes described as scarlet), wearing a laurel crown on his head and holding a branch. Before the march began the general would meet his troops to receive their praise.

In the Gospel of Mark, Christ is given a makeshift purple robe and a crown of thorns. Then the Roman soldiers mock Jesus by jokingly saluting him and calling him the King of the Jews. This is all similar but opposite in meaning, to the praise a Triumphator receives. And the wooden cross is a replacement for the branch.

How Jesus’s condemnation compares to a Roman Triumph.

Over time, the Roman triumph became the exclusive rite of the emperor and by the time of Jesus, it had several other aspects added to it. As the triumphator marched into the Forum on the Sacre Via, a sacrificial bull would accompany him.

The bull would be dressed in a purple (sometimes described as scarlet) robe and crowned in order to signify its identity with the triumphator. Next to the bull was its executioner, carrying the method of execution, a double-bladed ax.

When the Triumphator reached the Forum, he was offered a cup of wine, but he would refuse it. Instead, he would pour it on the altar or the bull itself to signify the blood that was about to be spilled.

In the Roman Triumphal march, the significance of the bull was that of a god, and its sacrifice was the god’s death in order to show the magnificence of the triumphator.

In the case of Jesus, he was offered wine to drink, but he refused.

Though Simon of Cyrene appears in the other gospels, in Mark’s gospel, the similarity to the bull and executioner is very clear. Jesus is both the triumphator AND the sacrifice. And Simon stood in for the executioner as he walked with Jesus, carrying the method of execution.

Is the Via Dolorosa mentioned in the Bible?

No, the Via Dolorosa is not mentioned in the Bible. This is because it is a Christian tradition that developed over time, rather than something that was gleaned directly from the Gospels such as communion.

In the Gospels, the trial and crucifixion narrative is told in Matthew 27, Mark 15, Luke 23, and John 18 and 19.

What does Matthew say?

Matthew mentions the mocking from the soldiers, but little to nothing about the journey from the Praetorium to the cross. He merely states “As they were going out, they met a man from Cyrene, named Simon, and they forced him to carry the cross.” (Matt. 27:32) He doesn’t even mention Simon’s sons.

What does Luke say?

Luke does not mention the mocking of the soldiers at the Praetorium, and the journey to the cross is the same as Matthew’s with a couple of short additions. He includes the large crowd that mourned for Jesus. And he notes Jesus’s interaction with the women of Jerusalem on his way to Calvary.

Luke writes,

“26As the soldiers led him away, they seized Simon from Cyrene, who was on his way in from the country, and put the cross on him and made him carry it behind Jesus. 27 A large number of people followed him, including women who mourned and wailed for him. 28 Jesus turned and said to them, “Daughters of Jerusalem, do not weep for me; weep for yourselves and for your children. 29 For the time will come when you will say, ‘Blessed are the childless women, the wombs that never bore and the breasts that never nursed!’ 30 Then

“ ‘they will say to the mountains, “Fall on us!”

and to the hills, “Cover us!” ’

31 For if people do these things when the tree is green, what will happen when it is dry?” (Luke 23:26-31)

What does John say?

John quickly describes the beating and mocking of Jesus by the soldiers in the Praetorium, but it happens before Jesus is sentenced. The journey to the cross is two sentences. He writes, “So the soldiers took charge of Jesus. Carrying his own cross, he went out to the place of the Skull (which in Aramaic is called Golgotha).” (John 19:17).

What does Mark say?

Mark on the other hand, spends 4 verses (Mark 15:16-20) describing how the soldiers mocked Jesus. And the mocking happens after he is sentenced. Which is important considering the comparison to the Roman Triumphal March. The ceremony has the general’s soldiers praising him after the senate vote and before the march. Mark specifically describes the soldiers falling to their knees to pay homage to Jesus in a mocking way.

Now don’t hear what I’m not saying. There were many ways that the Crucifixion narrative was similar to the triumphal march to begin with. We can see in the other gospels that the narrative is rather benign but they all tell the same story. All Mark did was tell the narrative through the lens of the triumphal march because of who his audience was.

Mark also describes who Simon of Cyrene was (Mark 15:21). Simon is referred to in the other gospels. And, his presence was certainly to suggest the wearing down of the procession on Jesus. However, Mark’s use of the event is consistent with the Roman Triumphal march. Jesus is the sacrifice and walking next to him is an official who carries the instrument of the sacrifice’s death.

Mark is the only one who mentions Simon’s connection with the community of believers. His sons are Alexander and Rufus, who the Roman Christians most likely knew. This would place Simon in a higher status than just a mere passerby. Someone who was divinely appointed for the purposes of the triumphal march.

Where does Golgotha fit in all this?

When Jesus reached Golgotha he was offered wine mixed with myrrh. Whereas, in the other accounts it is described as wine vinegar and offered while he was on the cross. In the triumphal march, the Triumphator was offered wine at the end of the march before the sacrifice was made.

The Roman Triumph ended at the Capitolium, where the temple to Jupiter was. The Capitolium was on Capitoline Hill which got its name during the construction of the temple to Jupiter. While laying the foundation, a human head was found with its features intact. It was thus proclaimed that the location was the head, or capita, of all Italy.

Like John, Mark also states Golgotha means “the place of the skull.” (Mark15:22). But in Mark’s case, he is specifically linking Calvary to Capitoline Hill. As well as the end of the Triumphal March where the bull will be sacrificed to honor the Triumphator.

All of this is pertinent because of where the Via Dolorosa we know today was developed.

If the Via Dolorosa is not mentioned in the Bible, how did it become a thing?

Though the path of Jesus’s triumphal march to the cross is not described in the bible, the start and finish are named. We know it started at the palace, or Praetorium, where Pilate stayed. And we know it ended at Golgotha or the place of the skull.

Early developments.

In the first, second, and third centuries, while the Roman Empire entered its late stages, Christians knew where these locations were. And, they often visited them to pay homage to Christ’s sacrifice. There’s even a legend that Mary, the mother of Jesus, would walk the route every day until her death.

Even after Hadrian renamed Jerusalem to Aelia Capitolina in 130 AD and built a temple to Venus (the Roman goddess of love) over the site of Golgotha; Christians still continued to pass down knowledge of these locations to their offspring. And the fact that the temple to Venus sat over the spot known to be Golgotha simply made it a marker for future generations.

In the fourth century, when Constantine established Christianity as the religion of the state, what had been practiced in solemn silence under the Romans, became outward expressions of faith.

On Holy Thursday, Christians would assemble on the Mount of Olives at the Eleona Church to commemorate the Last Supper. Today the site is known as the Mosque of the Ascension of Jesus. Christians would then walk down the mount to the Garden of Gethsemane.

After services at both locations, they would then march to the Holy Sepulchre for a dawn service. Though they followed a specific route, there was no attempt to ‘trace’ Jesus’s footsteps. It was merely an organized means to see several important sites in a single pass. This route naturally followed along the northern side of the Temple Mount where the Antonia Fortress was.

Changes to the route.

In the 8th century, the route had changed because both the city changed and the sites they wanted to visit changed. Instead of passing the Temple Mount to the north, they went along its southern side to the House of Caiaphas.

The next stop was the praetorium at the Church of Holy Wisdom somewhere in the Tyropoeon Valley. This church is not known today. And finally, they went on to the Holy Sepulchre. Note: The Tyropoeon Valley splits the western and eastern hills, but was filled in as the city grew west from the City of David (Eastern Hill) and the Temple Mount.

The impact of the Crusaders.

By the 11th century, public processions were outlawed by the Fatimids. In 1048, Emperor Constantine Monomachus restored the Holy Sepulchre and incorporated several small chapels signifying the passion narrative. This allowed Christians and pilgrims to commemorate the suffering of Jesus without having to go out onto the street. As a result, the memory of some of the locations waned.

When the Crusaders took control in the 12th century, the processions started again. However, Crusader intolerance for the Eastern church and its customs created tension and differing opinions about the path.

In 1169, the German monk Theodoric visited Jerusalem and located Pilate’s condemnation of Jesus on Mount Zion.

Recent archaeological finds on Mount Zion, or better put, the Western Hill, have reinvigorated scholarly interest in this being the actual start of the Via Dolorosa. However, Pilate’s house was considered to be near the Antonia Fortress by the Lion’s Gate. And this is the location of Jesus’s condemnation that won out.

An official tour is formed.

It wasn’t until the 14th century that the Franciscan custodians of the Holy Land began to develop a circuit of holy places though. The route started at the Holy Sepulchre and ended at the house of Pilate.

In the 15th century, Christian leaders started to develop a sense that the section between the Holy Sepulchre and the house of Pilate should be given a status of its own with important stops on the route itself. And with this, they determined that the route should go from the palace to the Sepulchre, rather than the other way.

By the 16th century, three stations had been identified. The first was Jesus’s encounter with his mother. The second was Simon of Cyrene taking up the cross while Jesus addressed the women of Jerusalem. And the third commemorated Veronica wiping the face of Jesus.

More stations were added over time, including one where Jesus falls, and another where some bystanders strike Jesus. At this time there were seven stations, and they were referred to as the “Seven Falls.”

European influence.

All of this had a tremendous impact on pilgrims and a few that returned to Europe instituted them in worship in their communities. In 1563, Jan Van Paeschen wrote his Spiritual Pilgrimage of Jerusalem as a reflection on the path. This was the first time the term ‘Way of the Cross’ was used.

In Europe, the ritual started to take on a life of its own. Churches and communities began to set up small versions of the Way of the Cross to commemorate Jesus’s triumphal march. As the custom grew in popularity, more stations were added. Eventually, the number rose from seven to fourteen.

As European pilgrims traveled to Jerusalem, what they knew to be the path back home clashed with what their Franciscan guides in Jerusalem were teaching. In order to avoid being shamed, the monks took on the Western version of the Way of the Cross, with its fourteen stations.

When did Christians begin walking the Via Dolorosa?

Technically speaking, Christians began walking the “Sorrowful Path” almost immediately. But not as a custom to commemorate Jesus’s triumphal march. The path was more of a means to get to the sites they wanted to stop at and pray over Jesus’s trial and sacrifice.

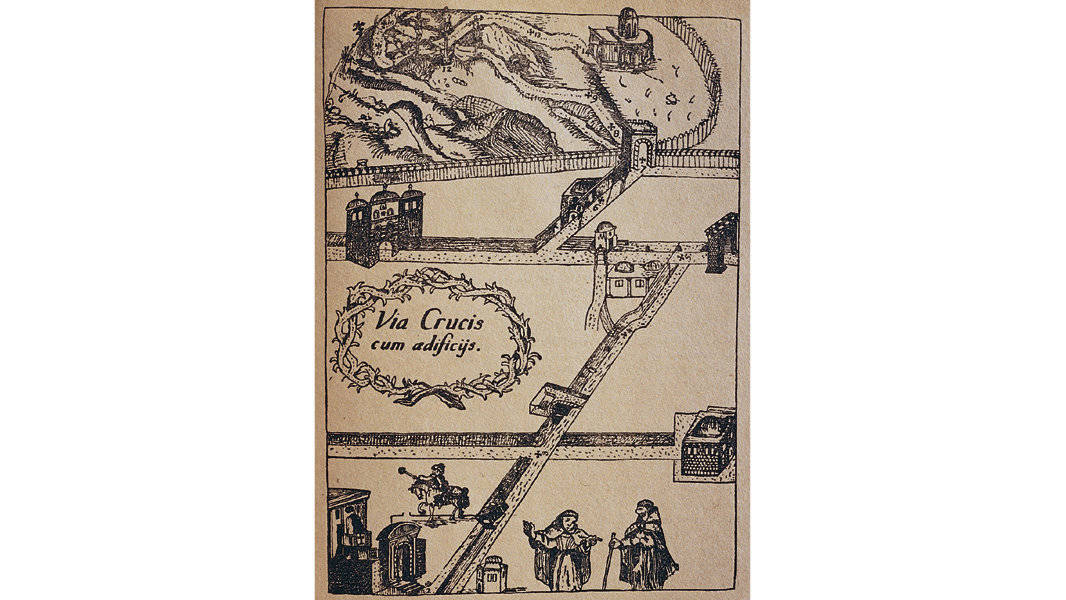

The path known as the Via Dolorosa that modern tourists walk every day reached its final form in the 18th century. Franciscan monk Elzear Horn recorded a visual depiction of the Via Dolorosa on a map of Jerusalem.

Where does the Via Dolorosa Begin?

Before I explain the answer to this question, let me say that the beginning of the Via Dolorosa is a cornucopia of confusion. So, I’ll try to keep everything straight.

The Via Dolorosa begins at Station 1, which is where Jesus was condemned to death. Tradition places this event at the Antonia Fortress. Which sat on the northwest corner of the Temple Mount.

The Omariya School.

Today the Omariya School sits on this location, as does the Chapel of the Condemnation and the Chapel of Flagellation which are in the courtyard across the street from the school. We have no archaeological evidence of where the Antonia fortress actually stood because the Old City is on top of any remains that could be underneath the streets and market. The only evidence that we have is from Josephus.

If you follow the Franciscan procession on Friday afternoon, you will start from the Omiraya School. But in the courtyard across the street are two chapels. The first one is to the left when you enter the courtyard and it is called the Chapel of the Condemnation. It corresponds with Station 1 of the Via Dolorosa where Jesus is condemned.

Definitely visit the Chapel of the Condemnation and if you can’t get into the Omariya School, start your journey on the Sorrowful Path here.

Head back towards the entrance to the courtyard and at the opposite end from the Chapel of Condemnation you’ll see the Chapel of the Flagellation. This is often associated with Station II of the Via Dolorosa, but the beating and mocking of Jesus is technically in between the Condemnation of Christ and Christ picking up His cross.

There are as many explanations for where Station I and II are as there are tour guides willing to give you their opinions. So don’t get too wrapped up in where the real beginning.

Where was the Antonia Fortress located?

In all actuality, whether you are standing in the courtyard of the Omiraya School or the courtyard of the two chapels (the Chapel of Condemnation you’ll see the Chapel of the Flagellation), you are at the location of the Antonia Fortress and its courtyard.

For ease of movement and to reduce confusion, just follow the disks with the Roman Numerals on them. When you enter the courtyard of the two chapels, the disk at the entrance has the Roman Numeral 1 on it for Station 1. So, you’re at the beginning.

Where does the Via Dolorosa End?

The Via Dolorosa ends at Station 14 which is the tomb of Christ. It’s not much of a tomb anymore, as the remnants sit inside the Aedicule located under the larger dome in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Inside the Aedicule you will find the slab of stone on which Jesus’s body was laid after he placed in the tomb.

Why do we celebrate the Via Dolorosa?

These objects have stories of their own, but we aren’t visiting the Holy Land for the sake of the Holy Land, we’re visiting because we want to connect with Christ on an organic level. And the surprising thing is that there is a plethora of locations and objects in the Holy Land that bring ALL of the Bible stories we know, to life visually and organically.

A visit to the Holy Land gives us organic touch points to the biblical narrative, and that can be tremendously reassuring. But even more important is that these touch points also bring us closer to God through physical experience with the land in which He interacted with His people.

When you visit the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, you will find many people kneeling and praying over the Stone of Unction. It is customary to kiss the stone or rub it with rosewater or oil and then wipe the stone clean on that spot with a cloth. It is said that the stone’s anointing transfers to the cloth and therefore the cloth now has healing powers.

If you want to partake in the tradition, I don’t see any reason not to. Traditions can be fun and despite its history can still be a form of worship. Personally, I like to place prayer notes between the stones in the Western Wall. It’s fun just trying to find a spot and then jamming it in so it sticks.

The question I’d ask yourself is, if Jesus is truly in your heart, do you need His power to be in an object for you to feel his presence or blessing?

Is the Via Dolorosa accurate?

The Via Dolorosa is not physically accurate because the landscape of the modern Old City of Jerusalem is not the same as it was in Jesus’s time. As noted above, by the 12th century, the landscape had changed so much that memory of some of the original processional sites was lost. Today, the street that the Via Dolorosa follows did not exist in the first century.

As far as the accuracy of the stations, only nine of the stations can legitimately be linked to the biblical narrative. The others are either customs that developed in Europe or, in the case of Veronica, is taken from another narrative in the Gospels.

What is the Via Dolorosa’s purpose?

The Via Dolorosa’s purpose is to pay homage to Christ’s sacrifice on the cross. It doesn’t need to be physically accurate. It’s a form of worship directed toward Jesus. And that is all we need.

For those that question Christianity for the presence of inaccuracies or arguments about historicity though, the fact that the Via Dolorosa has a history is telling. Arguments over locations in which archaeology and facts point to realities that can be referenced in the biblical narrative say more about legitimacy than one may think.

Disagreement over the artifacts, archaeology, and writings related to biblical history tells us that something happened here. And it happened at a time that matches with when the Bible says it happened. But it’s a 10,000-piece puzzle and we only have a thousand pieces so far.

The Passion Narrative is also incredibly complex. Far too complex in my mind for it to be conjured up. If we look at ancient religions and stories like the Roman and Greek gods, the Enuma Elish, or modern tails such as those we find in our own superhero lore; its readily apparent that human creativity does not have the capacity to create a story with the scope and depth that we find in the Bible.

What is the real Via Dolorosa?

After the establishment of the modern state of Israel in 1948, a surge of archaeological digging uncovered a large portion of the wall on the western part of the old city. What appears to be a small side gate can be seen about 500 yards south of Jaffa Gate. The gate has been filled in by stone, but remnants reveal something peculiar.

Excavations in the Citadel next to Jaffa Gate have revealed a large compound determined to be the place where Herod lived. In essence, a palace. This side gate would have been at the southern end of the compound.

A platform for Pilate to address the crowd.

The side gate appears to be less of a spot for traffic to enter and exit the city. Rather it appears to be a possible location where Herod and later Pilate conducted trials. Or, to speak to the people. The main entrance to the palace was on the inside of the security walls where space would have been tight and lacking the room needed to address large crowds.

It does not make sense that criminals would be taken into the palace for trial through the main entrance. The same would be true for commoners seeking an appeal from Herod or Pilate. But it does make sense that a gate structure on the outside of the city would be used solely for this purpose.

The side gate also allows for massive crowds to gather around to hear from the leader or watch a trial. Something that would most likely be prohibited from inside the palace.

Traditionally the Antonia Fortress has been thought to be Pilate’s residence while he was in town. But this does not make sense because a Roman official would not stay with the grunts in the barracks.

This side gate theory matches the claim by Theodoric in the 12th century that Pilate’s condemnation of Jesus happened on Mount Zion.

If this is the case, then the real Via Dolorosa started at this gate and headed north, straight to Golgotha. I would even add that the large crowd mentioned in Mark would have been facilitated more easily on this route than in the city.

Can you visit the place Jesus was crucified?

Yes, the stone in which Jesus’s cross was placed is inside the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. It is Station 12 of the Via Dolorosa and is located to the immediate right and up the stairs when you enter the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

There is some disagreement on whether it’s the actual stone or just the traditional site, but I would argue that there is a significant amount of archaeological and historical evidence that it is the site. For a more detailed discussion on this and the history of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, check out my post on the topic right here.

What happened to the cross after the crucifixion?

Was the cross re-purposed and used for another crucifixion? Was it burned by a couple of soldiers who wanted a bonfire to stay warm? The Bible does not tell us what happened to the cross after the crucifixion. But there is a tradition that has been passed down from the time of Constantine.

As the story goes, when Constantine’s mother, Helena, went to Jerusalem at his request, to find the tomb of Christ, she also found the remains of a wooden cross on the ground near the temple. She assumed that these remains were from the cross Jesus was crucified on. This cross is referred to as the TRUE CROSS.

Today a few small relics of the True Cross exist, however carbon dating sets them in the 11th century vice the 4th or even the first century. Today when a procession ends, the mock wooden cross your group carried is placed under the sign for Station 9. It is then picked up and returned to the start.

- What is the Via Dolorosa?

- Station 1: Jesus is condemned to death

- Station 2: Jesus takes up his cross

- Station 3: Jesus falls for the first time

- Station 4: Jesus meets his mother

- Station 5: Simon of Cyrene helps Jesus

- Station 6: Veronica wipes the face of Jesus

- Station 7: Jesus falls for the second time

- Station 8: Jesus meets the women of Jerusalem

- Station 9: Jesus falls for the third time

- Station 10: Jesus is stripped of his garments

- Station 11: Jesus is nailed to the Cross

- Station 12: Jesus dies on the Cross

- Station 13: Jesus is taken down from the cross

- Station 14: Jesus is laid in the tomb

References:

Is Veronica mentioned in the Bible? by gotquestions.org

Did Veronica really wipe the face of Jesus? by aleteia.org

The Via Dolorosa Station 8 – Jesus Meets the women of Jerusalem by jerusalemexperience.com

8th Station and The Daughters of Jerusalem allaboutjerusalem.com (no longer posted)

The Holy Sepulchre’s Stone of Unction by dannythedigger.com

Stone of Unction anointing by allaboutjerusalem.com (no longer posted)

Stone of Anointing by madainproject.com

The Stone of the Anointing by thesalvationgarden.org

https://www.theviadolorosa.org/stations (site no longer active)

The Via Dolorosa by holylandsite.com

Walking in the Footsteps of Christ by www.dolr.org

Via Dolorosa by seetheholyland.net

“Does the Holy Sepulchre Church Mark the Burial of Jesus?” by Dan Bahat. Biblical Archaeological Review May/June 1986.

“The Geography of Faith” by Jerome Murphy-O’Connor. Bible Review, December 1996.

“Jesus’ Triumphal March to Crucifixion” by Thomas Schmidt. Bible Review, February 1997.

“The Procession That Never Was: The Painful Way in Jerusalem” by F. E. Peters, Autumn 1985.