- Gates Main

- Jaffa Gate

- Zion Gate

- Dung Gate

- East Gate (also known as Golden Gate)

- Lion’s Gate

- Herod’s Gate

- Damascus Gate

- New Gate

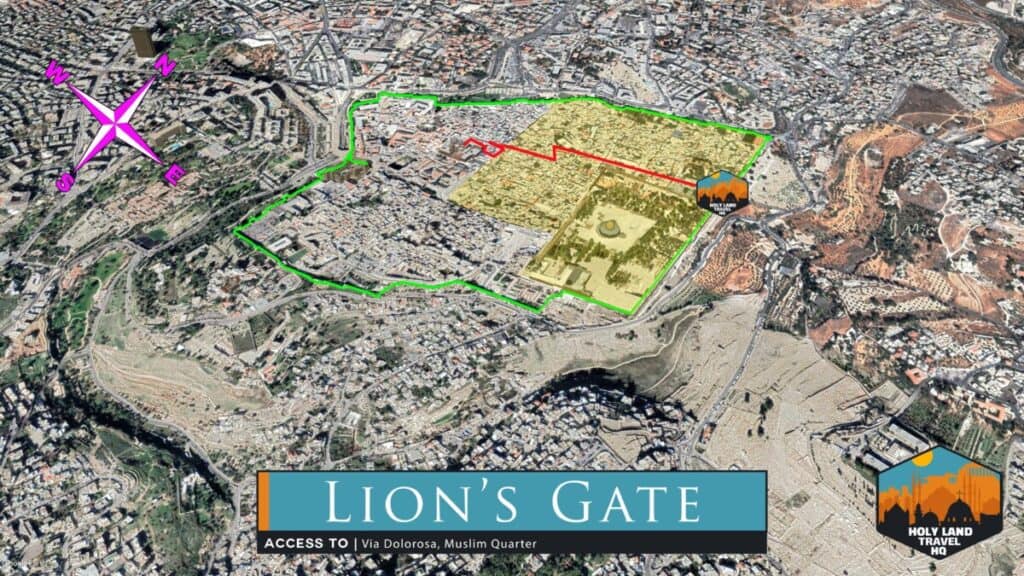

Location of Lion’s Gate.

Lion’s gate is located on the eastern wall north of the Temple Mount. It provides access to the Muslim Quarter, and the Via Dolorosa.

History of Lion’s Gate.

Lion’s Gate is aptly named because of the “lions” carved out of the stone in the wall on either side of the gate. There are two different stories behind these symbols. The first is that Suleiman had a nightmare that he would be eaten alive by wild animals if he didn’t finish the wall and secure the city. As a result, he had the lions carved out on the façade of the gate because it was the final gate to be constructed.

The second story is that the lions are actually not lions but rather panthers, which were the symbol of the Mamluk Sultan Baibars. The name Baibars in the Turkic language means “Lord Panther”, which prompted Sultan Baibars to use the animal as his heraldic insignia.

The Mamluks were a class of slave soldiers that became widely revered for their military prowess and in some cases rose to the rank of Sultan. Some factions also rebelled and seized power from their Islamic rulers.

Who was Sultan Baibars?

Baibars was born in the area north of the Black Sea into a family of Turkish nomads known as Kipchaks. His parents were killed by Mongol invaders and he was sold into slavery, eventually ending up as a military slave in the Egyptian Ayyubid Sultanate. He eventually rose to power by assassinating his boss, the Sultan of Egypt. He then made deals with the remaining Ayyubid Sultans in exchange for recognition as Sultan. His rule ushered in a period of numerous victories over the many crusader armies that entered the region.

Suleiman’s gate.

When Suleiman The Magnificent built Lions Gate, it is said that he had the panthers taken from a Mamluk building nearby. They were reused and integrated into the façade of the gate. Though there is no definitive motive for this, it is very possible that both stories are true. Suleiman was a Turk, an Ottoman Turk, but a Turk nonetheless. Sultan Baibars was a legend for his battlefield prowess, his victories over the Christian Crusaders, and his seemingly daunting physical appearance. He was also a Turk.

It is very possible that Suleiman, after having had his nightmare, had the panthers moved and incorporated into the gate to honor Baybars but also to inspire the legends of Baybars within the Ottoman troops.

The Lions’ Gate that we see today was built in 1538 and 1539 during Suleiman the Magnificent’s wall construction project. Suleiman intended for it to be named Bab el-Ghor or the Gate of the Depression because it faces the Jordan River Valley. But the name never stuck.

What is the Muslim name for Lion’s Gate?

Today Muslim and Christian Arabs have two names for the gate. The first name is Bab Sittna Mariam (باب ستي مريم), or the ‘Gate of Saint Mary.’ Or sometimes ‘Our Lady Mary’s Gate.’ This is because the Church of St. Anne sits inside the Lions’ Gate. The church dates back to the 12th century and was constructed by the Crusaders. It sits on a spot believed to be where the home of the Virgin Mary grew up. St. Anne was Mary’s mother.

In Islam, St. Anne is seen as a mystic and both her and Mary are highly revered by Muslim women. The Tomb of the Virgin, the traditional resting place of the Virgin Mary, is directly east of Lions’ Gate, down in the Kidron Valley next to the Garden of Gethsemane. This further justifies the naming of the gate to Bab Sittna Mariam.

A second Muslim name for Lion’s Gate.

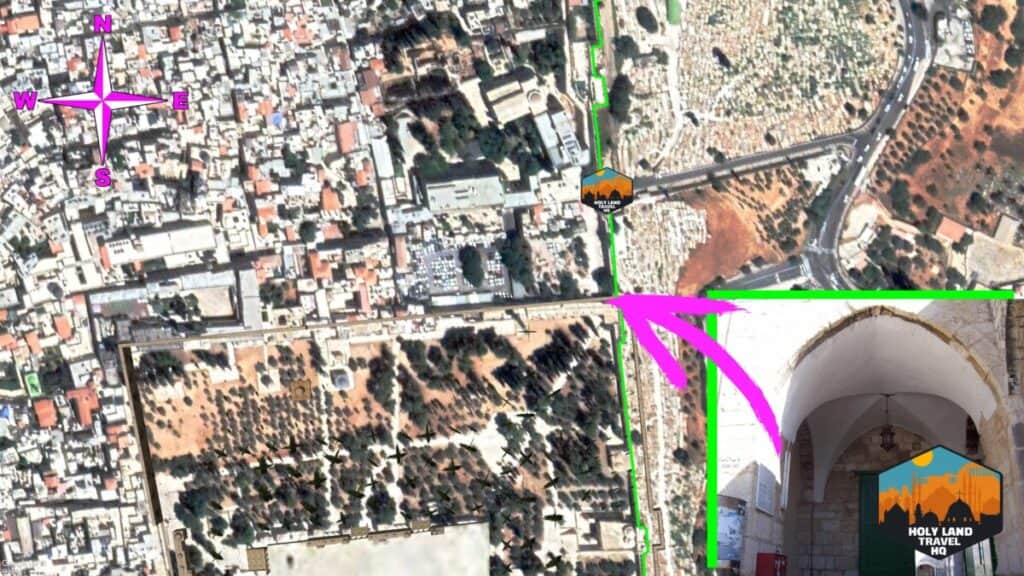

The second name that Muslims use for Lions’ gate is Bab el-Asbat (باب الأسباط) or the ‘Gate of the Tribes.’ The actual Gate of the Tribes is inside Lions Gate about 70 yards directly south through the el-Ghazali Square. It provides Muslims access to the Temple Mount on the Northeast corner. Because of its proximity, Lions’ Gate no doubt became a reference point for the Gate of the Tribes, eventually taking on its name as an extension of it. The “Tribes” being referred to are the original Twelve Tribes of Israel.

What is the Hebrew name for Lion’s Gate?

For Jews, The gate is known as Sha’ar Ha’Arayot (שַעַר הַאֲרָיוֹת), which just means The Lions’ Gate. Sometimes Lions Gate is also referred to as the Sheep Gate. The Sheep Gate mentioned in Nehemiah was thought to have been on the northeast corner of the city at the time. This is corroborated in the Gospel of John who describes the Sheep Gate next to the Pool of Bethesda. Bethesda has since been discovered just north of the Temple Mount next to the Chapel of St. Anne.

Neither Nehemiah nor John describe what the Sheep Gate was used for, but some legends say that it was the gate where sheep sacrifices were brought into the city. Or that a sheep market was located nearby where one could purchase sheep to sacrifice. The gate that we see today is not the original Sheep’s Gate. However, due to its location on the northeast corner of the Temple Mount, Lions Gate is sometimes referred to as the Sheep Gate.

What do Christians call Lion’s Gate?

Christians call the gate as Lions’ Gate, but have two other names for it as well. The second name is Jehoshaphat Gate. This is a reference to Joel 3:2 which states, “I will gather all nations and bring them down to the Valley of Jehoshaphat. There I will put them on trial.”

The Valley of Jehoshaphat is another name for the Kidron Valley, which runs parallel to the eastern wall. Many scholars believe that the passage in Joel describes the End Times prophecies associated with Golden Gate. Jehoshaphat Gate was also associated with an earlier gate that exited on the spot or near Lion’s Gate during the Muslim and Crusaders periods. Muslims referred to it as Jericho Gate.

A second Christian name for Lion’s Gate?

The third name that Christians have for Lions Gate is St. Stephens Gate. Stephen was one of the seven elders chosen to oversee the church in Jerusalem. His story is told in Acts 6 and 7. In Acts 7 he is questioned by the Sanhedrin and responds by telling the history of the Israelites. He ends with a condemnation of the Sanhedrin for killing Jesus. The Sanhedrin lash out and stone him to death.

The passage does not specifically state where Stephen was stoned to death, besides being outside the city. However, it was generally believed for many centuries that the location was north of the city outside what is known today as Damascus Gate. During the Crusader period, a Church was built to commemorate St. Stephen north of the city, and the gate was referred to as St Stephen’s Gate.

In the 12th century, after the Crusaders lost the city, the location of Stephen’s martyrdom moved to the east side of the city. Outside Lions Gate. Soon after, Christians began referring to Lions Gate as Stephen’s Gate.

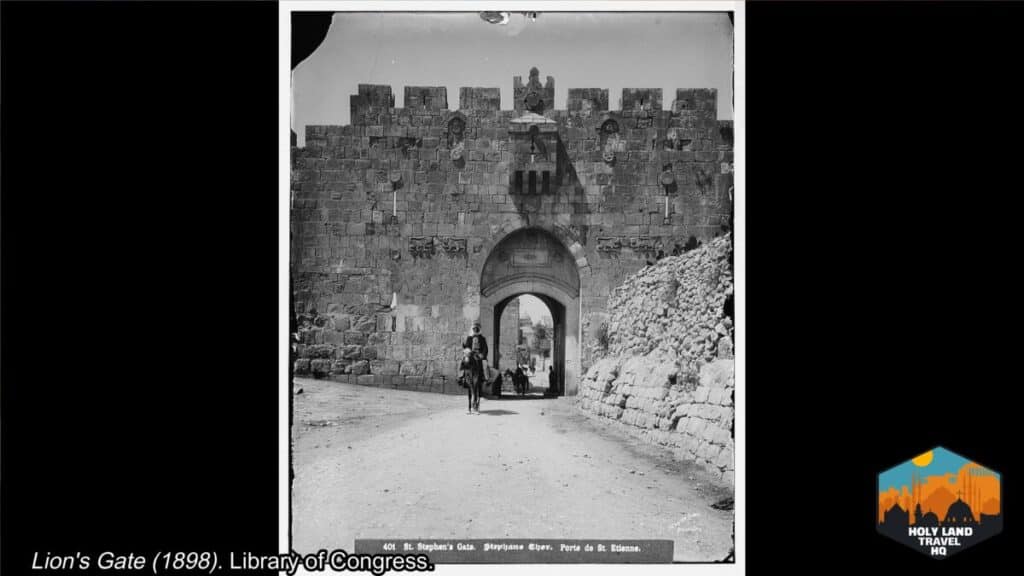

Layout of Lion’s Gate.

Lion’s Gate was built in the standard Ottoman gate layout with a 90-degree turn to slow down attackers. Today the back wall of the gatehouse has been removed. Entrance into the Old City is straight through the gate.

Though I could not find a date when the back wall of the gate was removed, pictures from the late 1800s AD show the wall in place. A picture from 1917 when the British took custody of the city shows the gate without the back wall. So it can be reasonably assumed that the back wall was removed in the very late stages of the Ottoman occupation.

An enclosed mashikuli balcony is located directly above the gate much like Zion Gate and Jaffa Gate. Again, a mashikuli is a balcony with an open bottom that allows defenders to drop unsavory things on attackers such as hot oil or excrement. In 2012, the embrasure in the outer wall of the mashikuli was repaired from damage due to damages sustained over time.

https://cnewa.org/magazine/bab-sittna-mariam-30784

https://biblewalks.com/LionsGate

https://historicalsitesinisrael.com/en/lions-gate-jerusalem

https://www.brown.edu/Departments/Joukowsky_Institute/courses/afterpharaohs2010/13950.html

https://jerusalemfoundation.org/old-project/lions-gate

https://madainproject.com/lions_gate

https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/14286b.htm

Hill, Craig Allen. “Golden Gate.” Edited by John D. Barry, David Bomar, Derek R. Brown, Rachel Klippenstein, Douglas Mangum, Carrie Sinclair Wolcott, Lazarus Wentz, Elliot Ritzema, and Wendy Widder. The Lexham Bible Dictionary. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2016.

Matev, Ami. “One Square Kilometer: The Old City – A Guide to the Sites. 2015. Old City Press.

Bahat, Dan. The Carta Jerusalem Atlas. Translated by Shlomo Ketko and Ada Yardeni. Third Updated and Expanded Edition. Jerusalem: Carta, Jerusalem, 2011.