You are planning your trip to the Holy land and you’d like to bring a piece of it home with you. Sand is boring, but an artifact sounds intriguing. Nothing says unique more than a genuine artifact from the time and place where Jesus walked. Am I right?

So, how can you buy antiquities in the Holy Land? In Israel, the best option is to purchase an object through an authorized antiquities dealer. But you still need to watch out for scams. In other countries, it’s best to avoid buying antiquities altogether. Either the laws are so strict the only market for antiquities is the black market. Or, the laws are so loose the US Government has gotten involved.

Generally, laws concerning the sale of antiquities are strict no matter where you go. So, you’ll want to know the laws to stay out of trouble.

There are disreputable practices all over the world for these types of transactions. Among them are fake antiquities on the open market. You can end up paying hundreds or even thousands of dollars for something that isn’t worth more than ten dollars.

Other scams involve the sale of stolen antiquities. In Israel, stolen antiquities won’t land you in prison if you can prove you got swindled. In other countries, possession of stolen artifacts, whether known or unknown can land you hot water.

The big question you need to answer is, do you really need an authentic artifact?

All links are direct.

What kind of artifacts are commonly sold on the open market?

The most commonly purchased items in Israel are clay pots, oil lamps, and coins. Coins tend to be an easy find and the cheapest to buy. They are also the easiest to fake.

Pots and lamps are much more difficult to fake and make a profit. Soil and air composition two thousand years ago was different than today. This affects the consistency and makeup of the potter’s clay. Archaeologists have gotten really good at identifying these details.

Other items of interest include weapons and Roman glassware. Bronze jars, jewelry, and other odds and ends can be found as well. These items can get pricey though, into the thousands of dollars.

In Turkey you will find Turkish carpets and what are referred to as ‘antiques.’ These are items determined to be less than 100 years-old in age. Other than these items, Turkey has some rather strict antiquities laws.

In Greece you can find all of the items listed above, however, most items are likely counterfeit or stolen. Unlike most countries in the region, Greece has struggled to pass and enforce antiquities laws. Because of this, they’ve looked to other governments to help them.

Egypt has a strict policy that prohibits all sales and movement of artifacts out of the country. Online marketplaces appear to be abundant, but, again, there is a high likelihood the items are counterfeit or stolen.

Know the time period you are looking for.

It’s important to understand what point in history you are trying to take home. If you are looking for something from the time of Jesus, you will want to look for Roman Era items. However, it’s going to be difficult to identify whether the item is from the intertestamental period or the First Century.

Abraham and Moses wandered the earth around 2100 BCE. The Middle Bronze Age spans from about 2100 BCE to around 1550 BCE.

If you are looking for something from the time of David and Solomon, you’ll want to keep your eye out for Late Bronze or Iron Age items. The Late Bronze Age spans the time from 1550 BCE to about 1200 BCE. While the Iron Age lasted from 1200 BCE to approximately 539 BCE.

The artifacts previously noted can be found across all of the periods here. So, you’ll need to know how to identify the key features of each age.

For some research on pottery identification from different eras throughout history check out this post from Peterborough Archaeology right here (direct link to petersborougharchaeology.org).

And here is an article on Roman pottery from mariamilani.com (direct link).

Also, what you will find in the markets will depend on the available supply at the time. So, be prepared with a few different items you might be interested in.

What these governments are doing to protect antiquities?

Every country in and around the Holy Land has antiquity divisions within their governments.

Israel established the Israeli Antiquities Authority in 1948 (direct link). The government passed a law concerning the treatment of antiquities in 1978.

In 1958 Egypt established the Ministry of Culture, which spawned the Supreme Council of Antiquities. The council lasted from 1984 until 2011 when it rebranded itself as the Ministry of State for Antiquities. Egypt passed its antiquities law in 1983.

Turkey formed its Ministry of Culture and Tourism in 2003.

And Greece established its Ministry of Culture and Sports (direct link) in 2013.

Antiquity laws have been passed by all of these governments because tourism is a large contributor to their economies. Their goal is to keep tourists coming but to make sure they don’t leave with the history that lured them.

A culture’s history is important to its identity. Dealers trying to make a buck and tourists looking to collect souvenirs of their travels can cause damage to that identity.

But, as we’ll see in a second, prohibition can cause some dire consequences. Such as black-market deals and illegal sales on the open market.

Israel appears to have the most comprehensive laws, allowing authorized dealers to sell antiquities on the open market.

Israel requires dealers to register their inventory. Registries don’t guarantee 100% accountability, but it helps the government have visibility.

Turkey and Egypt have strict laws, with no tolerance policies.

How to buy antiquities in Israel.

Purchasing a genuine artifact in Israel is relatively easy. Because its legal, dealers set up shop in the Old City and other tourist hotspots. So, you shouldn’t have a problem finding one. The question becomes, which one.

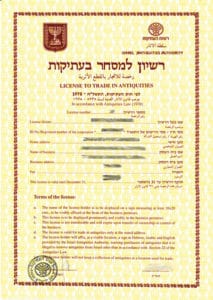

Dealers must register with the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) in order to sell. Obtaining a license is done yearly for about $550. Once they are certified a dealer must report their inventory to the IAA for tracking purposes.

An antiquities dealer license looks like this. (picture below)

If you are unsure if a dealer is legal, ask to see their license. Only authorized dealers are allowed to issue certificates of authenticity for artifacts. Certificates vary in format.

Ideally, you want to have an item #, item description, date, and business name. AS well as a stamp saying the business is an authorized dealer. Most certificates, unfortunately do not have the item # included.

Some shops sell items at fixed prices, while others will engage in bargaining. The ones that offer fixed prices do so because they are accustomed to westerners. This does not mean that they can be completely trusted, though.

Do your research before you travel to get an idea of what the different artifacts are selling for. If and when you do buy an artifact, make sure you walk away with a Certificate of Authenticity.

Zak’s Antiquities in the Old City is a well-known dealer among veteran tourists. I would still suggest you approach with a discerning eye even though he has a good reputation that he works to uphold. He’s a good place to start, but make sure to check out other dealers.

Baidun.com (direct link) is a website for a dealer located in the Old City on the Via Dolorosa. His supply is more opulent but can help with your research. Baidun does not list their prices, you have to contact him directly.

What do antiquity scams look like?

The tactics of scammers change as laws change. But there are still some common methods used over and over again because they are tried and true.

Common scams include the minting of counterfeit coins and the selling of stolen artifacts.

Let’s take a closer look at some of these scams.

Issues with ancient coins.

Coins are easy to fake because the materials are still available today, and cheap. It doesn’t take a lot of effort to make one look authentic either. Manmade imperfections make counterfeiting easy. But this doesn’t mean all coins are fake.

Pottery, on the other hand, is expensive to duplicate because it’s difficult to mimic aging, ancient textures, and ancient processes.

In the ancient world metal coins were weighed on the scale when purchasing goods by weight. Merchants would often scrape or clip the edges of coins in their possession to shave off some weight before recirculating them. This was a practice called ‘debasing.’

The merchant would then use the coins for non-weight-based transactions such as buying clothes. Coins had a monetary value and a weight value. The face value was not affected by the coin’s weight.

When buying products sold by weight, shaved coins meant customers received less than what they paid for. And a merchant’s supply went farther.

If you look at any US minted coin today, it will have a pattern of ridges around the edge. The reason for this stems from the practice of debasing. The ridges show that the coin has not been tampered with.

In the ancient world, a coin could sometimes remain in circulation for a hundred or more years. It probably changed hands thousands, if not tens of thousands of times.

This all means coins are really easy to fake. Imperfections can be easily covered up or missed upon close inspection.

If you see a coin you would like to buy, verify that the dealer is authorized to sell artifacts. Ensure they have a license. Ask where the coin was found. Keep in mind, coins are plentiful, so backstories are easy to fake too.

How to spot stolen artifacts and Antiquity laundering.

Another illegal activity is to sell stolen, but authentic artifacts. Like I said above, open markets keep artifacts off the black market. But they don’t prevent nefarious activity.

When the Antiquities law passed in 1978, there was a grandfather clause that allowed dealers the grace to sell anything they already had in their inventory.

Dealing can be a tough business. Merchants will want to make a buck wherever they can. So, dealers may turn to thieves who are looking to offload artifacts they picked up from a dig site.

Let’s say a dealer had an oil lamp in 1977 and it was labeled on their inventory with the number A23. The dealer knows that coins are easy to get, but they don’t make him that much profit. However, an oil lamp will.

Along comes a looter who obtained 2 lamps from a dig site he raided in the middle of the night. He sells them directly to the dealer. The looter gets more than what he would have gotten through legal means. The dealer pays less because there are no processing fees or taxes.

The next day a tourist wants to buy the oil lamp on the shelf. The dealer tells the tourist it’s a very old item and has been on his shelf for decades. The tourist is enthralled and jumps at the chance to buy an artifact so many before him have passed up.

The dealer does not issue a receipt. But he does issue a Certificate of Authenticity for the real artifact. The tourist doesn’t care, he got his souvenir and his certificate.

As soon as the tourist leaves, the dealer puts another oil lamp on the shelf with the label A23 on it. He tells the next tourist the same story.

The Tour Guide / Antiquity Dealer.

In 2011, American tour guide and retired Mormon university lecturer John Lund was arrested by the IAA. He was caught selling artifacts to members of his tour group. (Direct link to reference @ biblicalarchaeology.org).

Lund claimed he did not know of the Antiquity laws in Israel. He further claimed that the checks from his group members to him were to pay off remaining balances for the tour.

Whether Lund was guilty or not, it doesn’t really matter. The moral of the story is, don’t buy artifacts from your tour guide. Or any illegitimate sources.

Research prices. Go to the market. Check to make sure the dealer has a license. Get a Certificate of Authenticity.

Digital systems and the human factor.

Today, the IAA requires dealers to take photos of each item in their inventory from different angles. Images are then uploaded to a government website where dealers report their inventories. (direct link to reference @ biblicalarchaeology.org).

The use of digital inventory tracking has reduced the frequency of antiquity laundering, but not completely. There are still ways to get around it, such as switching an item out with an identical yet non-inventoried item while packaging it up for you.

Whether the artifact is the one on the shelf or not, you will most likely still get an authentic artifact. The dealer isn’t trying to swindle you, but rather the government. As long as you have a Certificate of Authenticity, you have proof you were trying to be legit.

The bottom line is that if you don’t feel comfortable, politely decline to buy and go somewhere else.

How merchants prey on unsuspecting tourists.

If you’ve been to the Middle East or Asia, you have probably had to barter. Bartering has been a way of life for many cultures since the dawn of time. It’s not an unethical practice, but there are some unethical tactics that merchants employ.

Not surprisingly, God actually has something to say about how to buy and sell ethically in the book of Leviticus. Western Society is subsequently built off of those values.

For example, the practice of debasing is why every US state has a Department of Weights and Measures. When you go to the gas station there will be a sticker on each pump identifying its most recent inspection.

Today, non-western merchants are used to westerners and offer fixed prices on common items. Like T-shirts, food, bags, shoes, dinnerware, and similar items.

With uncommon items, bartering is still a thing. If you buy a carpet in Turkey, you will need to barter.

Shady merchants in the non-western world often have two prices in which they start the bartering. One for their own people and another for tourists. The tourist price is often 3-times the value of the item.

A tourist who is wise to the game can talk them down to the real price.

An unsuspecting tourist will try to talk the merchant down, but will often land at a price that still over-values the item. The merchant will then make the tourist feel they are getting a bargain.

Honest merchants don’t play these games. However, they can still come across like a swindler to a tourist who is conditioned to think all bartering is bad.

How to prepare to barter.

If you are looking for an item that will require bartering, there are a few things you can do to prepare.

Do your research. If you are looking to buy a carpet in Turkey, know how carpets are constructed. Also know the value of the materials used. This is important because not all carpets are equal. You can possibly pass on a gem thinking it costs too much when its value is spot on.

Your research should not only give you insight into the quality of the items but also what you are looking for. If you want a carpet for your dining room, know the size. Estimate the value range and set a budget.

Get advice. Ask your tour group leader and your tour guide for guidance. Use their advice to make sure your expectations are realistic.

To find more on bartering, check out this article on the subject. (Direct link to moneycrashers.com. No affiliate links.)

How to avoid bartering.

This might seem obvious but stick to known tourist-friendly venders. I’ve traveled the world a lot. I don’t buy much, but I’ve traveled with people who do. Invariably, there is always a guy or gal who wants a unique buying experience. They don’t want to buy from the “tourist-friendly” shop. They want the shop where the locals go.

If you are a veteran traveler, feel free to buy where you want. If you are new to this, I recommend the tourist-friendly shop. They often get their inventory from the same suppliers, or they’ve built their business around the tourist as a customer.

In Turkey, for example, there are carpet factories that are stops along tour routes. Particularly in and around Selcuk, Turkey (google maps link).

Yes, these factories have deals with tour guides. But they also aren’t going to ruin those deals by taking advantage of the customers that tour guides bring in. The carpets are still handmade and high quality.

How to Buy Antiquities in Turkey

Unfortunately, you cannot buy antiquities in Turkey. They don’t allow the export of artifacts. However, you can buy antiques and carpets. An antique is defined as an item of less than 100 years-old.

Knowing this, beware of anyone selling artifacts or items that appear to be artifacts.

How to Buy Antiquities in Greece

The simple answer here is, don’t do it. Getting antiquities out of Greece is easier than Turkey. Probably really easy. So easy, in fact, that Greece asked the United States to help them combat the practice of artifact smuggling.

The US Department of Homeland Security responded in 2016 and stepped up measures to stop the import of Greek antiquities. Check out this article on the issue (Direct link to savingantiquities.org.)

Greek and Roman antiquities are some of the most highly sought-after items on the market. As a result, these countries have struggled to protect their history. This is especially true with Greece, where the struggling economy has lured lawmaker’s attention away from antiquity smuggling.

In Israel the law requires dealers to communicate whether an artifact is fake or not. In Greece, this is not the case. So, if you find yourself in an antiquities shop, it’s a good bet that the items in their inventory are either stolen or fake.

If you really want an artifact, I recommend seeking out authentically counterfeit artifacts. As in, the dealer is purposefully selling fake items at legitimate prices.

Unknowingly buying stolen artifacts and bringing them home can turn into a nightmare. With the US Department of Homeland Security cracking down on artifact smuggling, you don’t want to chance it.

Why do stolen artifacts end up on the open and black market?

Archaeology has been around for a long time. But, good archaeology has not. In the last 100 years technology and the ability to explore our world has vastly improved.

Museums around the world have ballooned with artifacts and historical items. Many museums have vast warehouses with hundreds of thousands, if not millions of items in their inventory now. Unfortunately, they have limited resources to restore every item.

Even with large inventories, museums are only able to display small percentages of their items at a given time. Over the years, as more artifacts have been discovered, museums have had to turn some away. Many museums turn thousands of artifacts away every year.

As a result, many museums have developed acceptance criteria. They need to know how an artifact was obtained. They must figure out if it is authentic or not. And they have to determine if it adds value to their collection.

If an artifact does not meet the criteria, the only place for it to go is in the marketplace.

Thieves looking to make money by selling a stolen artifact to a museum often turn to black marketeers. As well as dealers looking to fill their inventory.

When an artifact is outside the museum system, the only line of defense a government has is customs enforcement.

If the museum won’t take it, who cares if it leaves the country.

The main argument against buying a genuine artifact and taking it home is that it encourages unethical practices.

One could argue that buying a coin doesn’t do much harm since there are so many out there. It’s the more unique, larger artifacts that foster nefarious activity.

When perusing the antiquities market, you need to ask yourself a question. Do you really need an authentic artifact to remember your trip?

Knowingly buying a fake artifact is not a bad thing.

Whenever I travel, the only souvenir I buy is a postcard. I don’t want to waste my time looking for something unique. Or waste money on a superfluous object which may or may not connect me to my memories of the trip.

When I went to the Holy Land for the first time, I wondered if I should break my rule and get something. I thought that maybe I wanted a souvenir that would connect me to the time and place of the Bible.

This is crazy talk though. Walking the locations referenced in the Bible is more than enough to make that connection. So do pictures. And prayer. And… well… reading your Bible.

For some people, having an authentic artifact can be a status symbol. And that is a dangerous desire to have if you are a believer.

Other people just like to buy souvenirs. If that’s you, and you’re looking to buy an artifact; fake artifacts are not bad souvenirs. If you buy a snow globe in New York, why not buy a fake oil lamp in Israel. Or a fake vase in Greece.

The only trouble you will encounter is thinking a counterfeit artifact is real and paying real prices for it. If taking home an artifact is your goal, I recommend seeking out authentically counterfeit artifacts instead of real ones.

Ask around. See what they say, or where they tell you to go. You might get some suspicious eyes, but overall, it can’t hurt. Tell them you don’t want to spend the money on a real one.

In the end, you can buy authentic antiquities if you want, but there are a lot of ethical issues involved. There are also a lot of laws and nefarious activities which can land you in trouble.

References

https://archive.archaeology.org/online/features/schultz/intllaw.html

https://www.aladdinrugs.com/history.html

https://www.moneycrashers.com/how-to-barter/