- Gates Main

- Jaffa Gate

- Zion Gate

- Dung Gate

- East Gate (also known as Golden Gate)

- Lion’s Gate

- Herod’s Gate

- Damascus Gate

- New Gate

How old is Jerusalem?

Jerusalem is one of the oldest cities in the world, with archaeological finds dating as far back as 3300 BC. Since its founding Jerusalem has been conquered, sacked, re-conquered and fought over almost endlessly. But it’s also been the focal point of God’s interaction with His people, and the place where His son, Jesus walked as a mere human.

Through all of this turmoil the city of Jerusalem has not always looked the same. It’s city walls, gates, and neighborhoods have expanded and contracted as its culture ebbed and flowed. Today, Jerusalem looks very different than it did even a hundred years ago. And most likely drastically different than it looked in the time of Jesus.

So, how did the city of Jerusalem change over the years? Let’s take a look at the gates of Jerusalem’s Old City and find out.

Jerusalem in the Bronze Age (3300-1200 BC)

Through the 1970s and 1980s, famed archaeologist Yigal Shiloh, worked in the area that today we call the City of David. In his excavations, he was able to find structural remains from the Early Bronze age, or roughly 3300 BC.

At this time in history, Jerusalem was occupied by Canaanites. We don’t get a name for the city though until the time of Abraham, around 2000 BC at the earliest. In Genesis 14:18 Abram meets with Melchizedek, the king of Salem. Salem comes from the Hebrew root word Shalom (‘Salem’ שָׁלֵם -> ‘Shalom’ שַׁלוׄם), which means ‘peace.’

At the time of Joshua or around 1400 BC, the city was referred to as ‘The Jebusite City.” And later in Judges, it’s referred to as Jebus, which would have made it the city of the Jebusites.

Whatever its name was before David conquered it and established his reign there, not much remains that gives us a clue as to how the city looked.

It isn’t until the time of Solomon and the First Temple period that we get any idea for how many gates there were, and what their names were. At this time the city occupied the southeastern hill exclusively. And had a population of about 2,000 people.

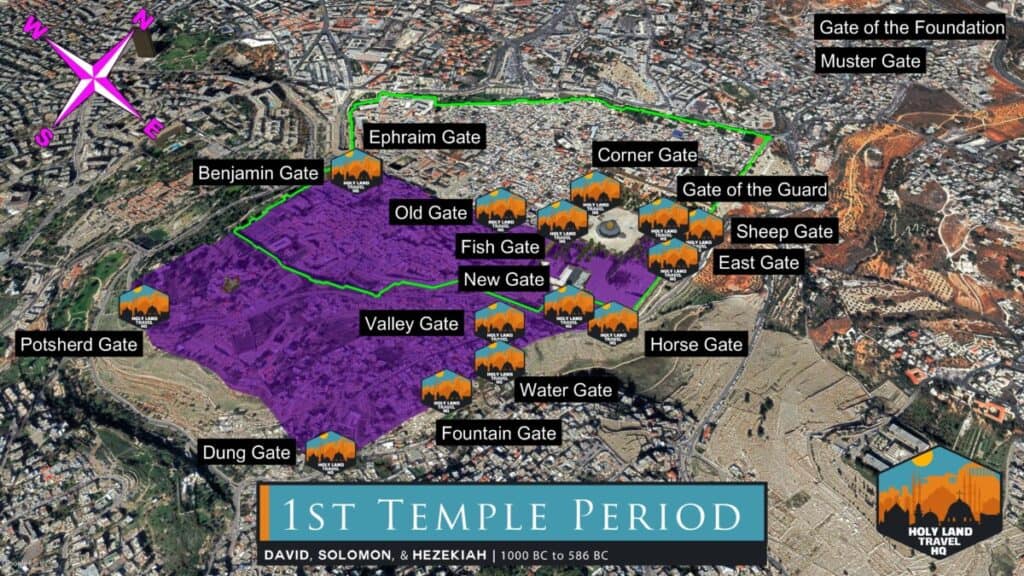

The Gates of Jerusalem’s First Temple Period (1000-586 BC)

By the end of Solomon’s reign, the city had grown to about 5,000 people and had expanded north with the construction of the Temple Mount. The Bible makes note of 17 gates at the time of David and Solomon, some of which scholars have hypothesized on their locations due to how they are described in the text.

Many of the gates simply cannot be placed because the biblical narrative is telling a story and not providing an architectural history. Most of the gates are discussed in the book of Nehemiah, though some are referenced in Kings, Chronicles and Jeremiah as well. When Nehemiah returns to rebuild Jerusalem in 539BC, he assesses the city wall and its gates. Scholars rely on Nehemiah because the list is so exhaustive but also because these were the names that would have remained in the corporate memory of both the exiled and remaining population. Hence, they were most likely the same names from the time of Solomon.

Here is a list of the gates.

- Ephraim Gate: location unknown. Most likely on the north wall. Probably the northwest corner, since Ephraim was north of Jerusalem. (2 Kings 14:13; 2 Chr 25:23; Neh 8:16; 12:39)

- Corner Gate: location unknown. Possibly the northwest corner of the Temple Mount. (2 Kings 14:13; 2 Chr 25:23; 26:9; Jer 31:38; Zech 14:10)

- Gate of the Foundation: location unknown. (2 Chronicles 23:5)

- Fountain Gate: likely located in the eastern wall on the southeastern hill, near the pool that was fed by the Gihon Spring. This would not be the Pool of Siloam. The original gate may have been Canaanite. (Neh 2:14; 3:15; 12:37)

- Valley Gate: likely located on the western side of the southeastern hill, leading to the Tyropoeon Valley, also known as the Central Valley. Archaeological research in this area revealed a gate complex dating to this period. The original gate may have been Canaanite. (2 Chronicles 26:9; Neh 2:13, 15; 3:13)

- Fish Gate: possibly located on the NW side of the Temple Mount. This would be the gate where the fish market was located. Also, this would be the gate that is referred to when people call the modern day Damascus Gate the Fish Gate. (2 Chronicles 33:14; Neh 3:3; 12:39; Zeph 1:10)

- Dung Gate: located at a southerly point of the city, much farther south than today’s Dung Gate. (Neh 2:13; 3:13–14; 12:31)

- Sheep Gate: Possibly on the north or northeast section of the city wall, perhaps at the Temple Mount. (Neh 3:1, 32; 12:39)

- Old Gate: possibly located west of the Temple Mount, near the Fish Gate. Might be an alternate name for another gate. (Neh 3:6; 12:39)

- Water Gate: possibly located at the source of the Gihon Spring. (Neh 3:26; 8:1, 3)

- Horse Gate: possibly located on the east side of the Ophel near the Temple Mount. (2 Chronicles 23:15; Neh 3:28; Jer 31:40)

- East Gate: Located on the Eastern wall of the Temple Mount. (Neh 3:29)

- Muster Gate: location unknown. (Neh 3:31)

- Gate of the Guard: location unknown. Possibly on the north wall or the northernmost east wall. (Neh 12:39)

- New Gate: connected to the king’s palace. Possibly located near the Temple Mount. Due to the name, the gate may also be an alternate name for another gate. It is not associated with the modern New Gate. (Jer 26:10; 36:10)

- Benjamin Gate: possibly located on north wall of the city. It could also be an alternate name for the Ephraim Gate since both tribes were north of Jerusalem. (Jer 20:2; 37:13; 38:7; Zech 14:10)

- Potsherd Gate: most likely located on the south wall, given that Jeremiah was facing the Hinnom Valley when he exited the gate. (Jer 19:2)

By Hezekiah’s reign the city had expanded west and grown to a population of about 25,000 people. When Nehemiah returned to take governorship of Jerusalem, the size of the city had shrunk back to it’s Solomonic size with a population of 4,500 people.

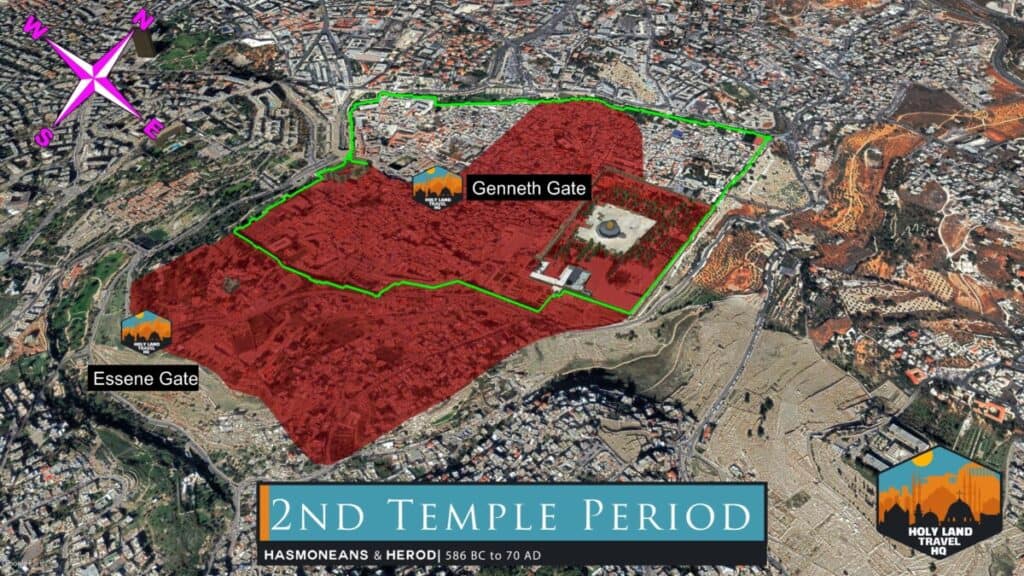

The Gates of Jerusalem’s Second Temple Period (586 BC – 70 AD)

By the Second Temple period, the city had grown and expanded. Under the Hasmoneans, it expanded west again and the population increased to roughly 30,000. By the time of Herod the city expanded north with a population of 40,000 people. Though it is likely that some of the gates that were present in the First Temple Period were still around in the Second Temple period, after Nehemiah’s governorship we don’t get much discussion on the gates until we reach the New Testament. Along with a little bit of information from Josephus.

In Josephus’s Wars of the Jews, only two gates are mentioned. The Gennath Gate and the Essene Gate.

Josephus places the Gennath Gate along a northern fortification line west of the Temple Mount. Scholars have noted that the word gennath is a Greek transliteration of the Hebrew word for ‘garden’ (גִּנַּת). Scholars place this gate on the northwestern hill where a quarry and garden was located. The quarry and garden in question would be none other than Golgotha.

Josephus places the Essene gate on the southernmost point of the southwestern hill, or what is known today as Mount Zion. Recently a gate dating to the Second temple period was discovered and excavated next to the Protestant cemetery located on the grounds of Jerusalem University College.

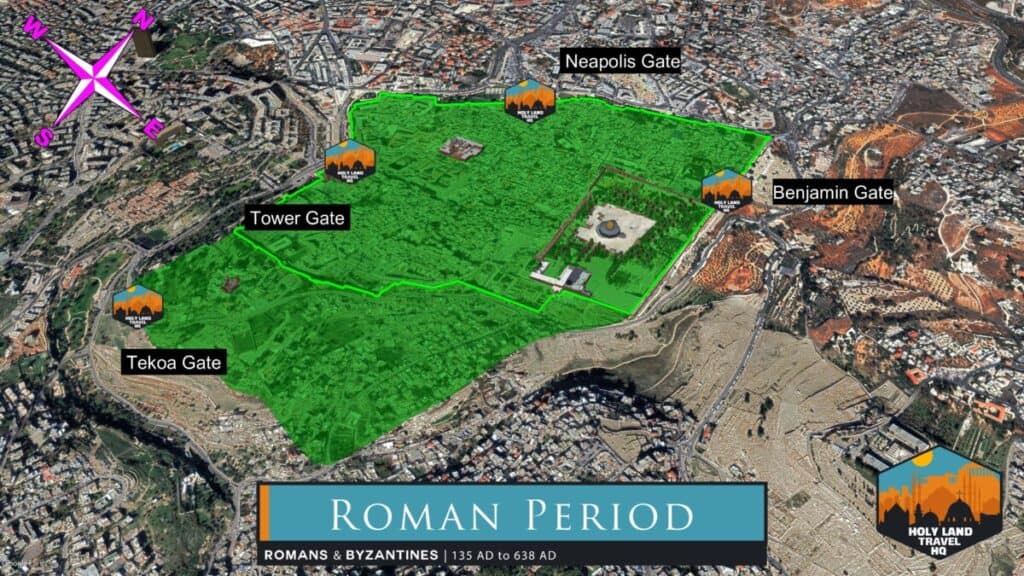

The Gates of Jerusalem’s Roman Period (135-638 AD)

As we know, the Romans sacked Jerusalem and set it ablaze in 70AD after the Jewish revolt. By this time the city had expanded north even more, beyond the walls that we see today. And the population doubled to around 80,000 people.

In 135AD, after the second Jewish revolt (also known as the Bar Kokhba Revolt), Rome renamed Jerusalem to Aelia Capitolina and renamed the land of Israel to Palestina after the Israelites former enemy, the Philistines.

By 135AD Jerusalem lacked fortifications, but it is likely that some of the gatehouses and structures or their foundations remained. This is because Rome wanted to deny any insurgency from gaining control and using the fortifications.

Christian pilgrims visit the Holy Land.

The only records that scholars have of any gates during this period are from pilgrim accounts. Three pilgrims provided data on what they saw when they visited. The first was an anonymous pilgrim from Bordeaux, France around 334AD.

The second was Theodosius, a pilgrim from the region of Cappadocia in what is modern day Turkey. He made his pilgrimage in 451AD. As a monk he founded the cenobitic way of monastic living in the Judean desert.

A third individual was Bishop Arculf, a Frank bishop from Gaul who traveled to the Holy Land around 670AD.

Between the three of these men, four gates were named.

- Neapolis Gate: located on the north wall where the road led north to the Roman city of Flavia Neapolis. Today this city goes by its modern Arabic name of Nablus. Inside Neapolis gate was a semi-circular public square with a column in the middle with a statue of Hadrian on top of it. The gate itself was built by the Romans as a victory arch for suppressing the Jewish revolt in 135AD. The statue was erected to honor Emperor Hadrian, who had changed the name of the city and the province in order to spite the Jews and Romanize the city. During the Islamic periods, the gate became known as the Gate of the Column. In the 1980s, remains of the roman gate were found under the structure of today’s Damascus Gate.

- Benjamin Gate: according to Theodosius, the gate was located on the east wall, just north of the Temple Mount. There is no indication that this gate is associated with the modern-day Lion’s gate though.

- Tower Gate: located on the west wall. It was named after the towers that Herod built in his palace compound. Later gates in this location were the Gate of David and the Modern Jaffa Gate.

- Tekoa Gate: scholars sometimes associate this gate with the Gate of the Essenes because it faced south. Bishop Arculf refers in his account to a gate he called the “Tekoa Gate” because it faced south towards Tekoa.

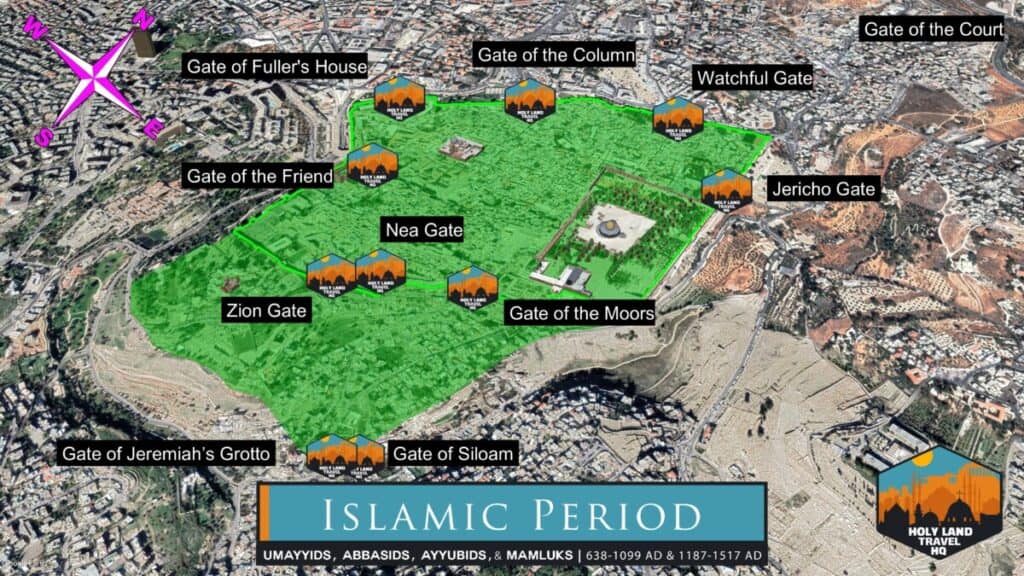

The Gates of Jerusalem’s Islamic Period (638-1099 AD & 1187-1516 AD)

The Islamic period covers four different Islamic occupations. The first two were the Umayyids and Abbasids between 638AD and 1099AD. The third was the Ayyubids between 1187AD and 1250AD. And the fourth was the Mamluks between 1250AD and 1517AD

Unlike the Roman period, scholars have a lot in terms of information on gates and names through the whole Islamic period. They have the account of Bishop Arculf in the 7th century AD, and the account of the Arab geographer Al-Muqaddasi from the 10th century AD. There are also several Islamic sources and lesser-known Christian pilgrimage accounts.

- Bab el-Amud (“Gate of the Column”): located on the north side of the city. The primary northern gate, it was named because of the large column with a statue of the emperor Hadrian on top of it. The modern-day Damascus Gate sits on the spot where the Roman and Muslim gate once stood.

- Bab es-Sahira (“Watchful Gate”): located on the eastern section of the northern wall. It was located in the same spot as the Ottoman gate known today as Herod’s Gate. It was named for the Muslim cemetery, Es-Sahira, located just northwest of the gate.

- Bab Ariha (“Jericho Gate”): located on the northern section of the eastern wall, just north of the Temple Mount. Today, Lion’s Gate sits on or near the spot where Jericho Gate was located.

- Bab el-Maghariba (“Gate of the Moors”): located on the eastern section of the southern wall of the city. The gate was established in the Mamluk period; it was originally named for the North African Muslims who settled this area of Jerusalem in the 16th century AD. This gate is not associated with today’s Mughrabi Gate, which is the main entrance for non-Muslims onto the Temple Mount. However, that gate is aptly named for similar reasons.

- Bab Silwan (“Gate of Siloam”): located on the eastern fortification line of the southeastern hill and was the city’s exit to the Kidron Valley in the vicinity of the ancient Pool of Siloam. The gate was named for the Arab village of Silwan, which was in existence by the 10th century AD.

- Bab Jubb Aramiyya (“Gate of Jeremiah’s Grotto”): located at the southern tip of the southeastern hill.

- Bab Sahiyun (“Zion Gate”), later Bab Harat el-Yehud (“Jewish Quarter Gate”): located in the western section of the southern wall. The foundation of this gate was discovered approximately 50 to 100 yards east of the modern Zion Gate.

- Bab Mihrab Daoud (“David’s Oratory Gate”), later Bab el-Khalil (“Gate of the Friend”): located as the sole gate on the western wall. Though it was not located on the same spot as today’s Jaffa Gate, it was in the same area and provided the same access.

- Porta ville fullonis (“Gate of the Fuller’s House”): located on the northern wall in the northwestern corner of the city

- Bab el-Balat (“Gate of the Court”): location unknown.

- Bab et-Tih (“Gate of the Desert Wanderings”?): location unknown. This gate is also mentioned by Muqaddasi. However, Muqaddasi’s spelling of the gate may be incorrect; if so, and the title emended to Bab en-Niah (“Nea Gate”), the gate’s name would reference the 6th century AD Nea Ekklesia Theotokos (“New Church of the Theotokos”) on the southwestern hill.

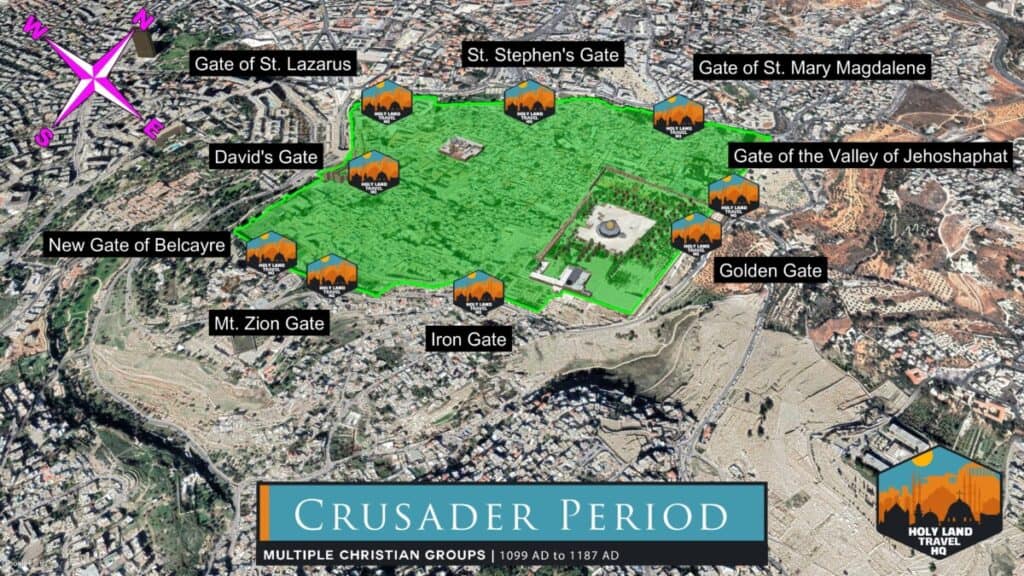

The Gates of Jerusalem’s Crusader Period (1099-1187 AD)

- Gate of St. Lazarus: located on the western corner of the northern wall in the vicinity of the Church of St. Lazarus.

- St. Stephen’s Gate: Crusader name for the Roman gate on the northern wall known as the Gate of the Column. The Crusaders called it “St. Stephen’s Gate” for St. Stephen’s Church located north of the city. The modern-day Damascus Gate sits on the spot where the Roman and Crusader gate once stood.

- Gate of St. Mary Magdalene: located on the eastern section of the northern wall in the vicinity of the Monastery of St. Mary Magdalene. This gate is thought to have been located in the area where the modern-day Herod’s Gate now sits.

- Gate of [the Valley of] Jehoshaphat, also called the “Gate of Olives”: located on the eastern wall of the city. This alternative, Crusader-era name for the Jericho Gate refers to the Kidron Valley, which had been called the Valley of Jehoshaphat as early as the Byzantine period. Today, Lion’s Gate sits on or near the spot where the Gate of Jehoshaphat was located.

- Golden Gate: The Golden Gate was only used twice a year in Christian ceremonies, but otherwise remained closed. This is the same gate that we see today.

- Gate of the Tannery, also called the “Iron Gate”: located on the eastern section of the southern wall, in the vicinity of the present-day Dung Gate. Today it is known as the Tanner’s Gate.

- Mount Zion Gate: located to the east of the Ottoman Zion Gate.

- New Gate of Belcayre: located on the southern wall of the city’s southwestern corner. The gate’s name refers to the suburb of Belcayre, located just inside the gate.

- David’s Gate: located in the vicinity of the modern-day Jaffa Gate.

References:

Barry, John D., David Bomar, Derek R. Brown, Rachel Klippenstein, Douglas Mangum, Carrie Sinclair Wolcott, Lazarus Wentz, Elliot Ritzema, and Wendy Widder, eds. The Lexham Bible Dictionary. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2016.

Matev, Ami. “One Square Kilometer: The Old City – A Guide to the Sites. 2015. Old City Press.

Ritmeyer, Leen. The Quest: Revealing the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. Jerusalem: Carta, Jerusalem; The Lamb Foundation, 2015.

Edersheim, Alfred. The Temple, Its Ministry and Services as They Were at the Time of Jesus Christ. London: James Clarke & Co., 1959.